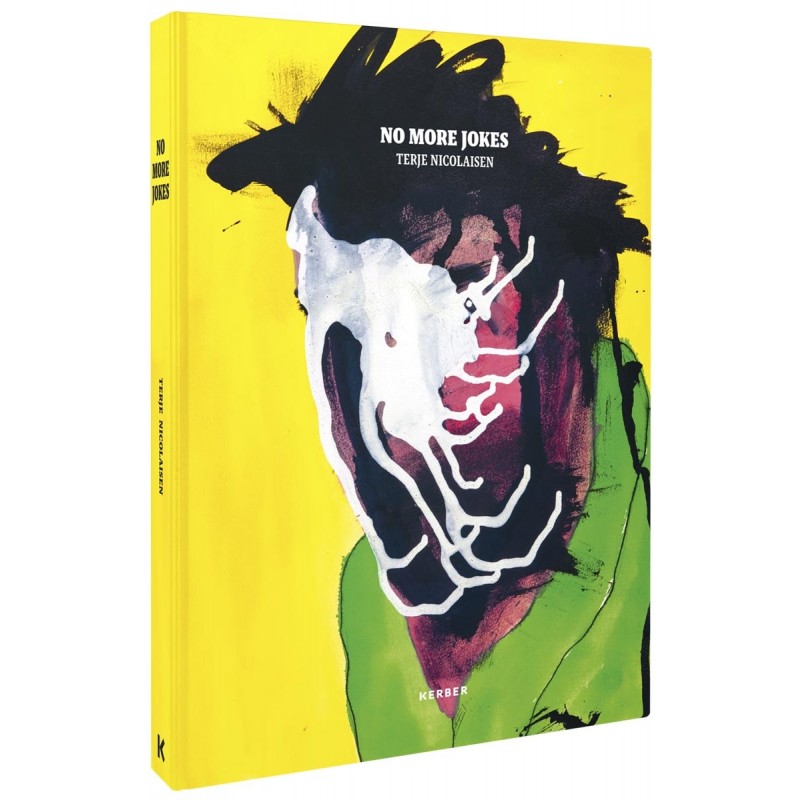

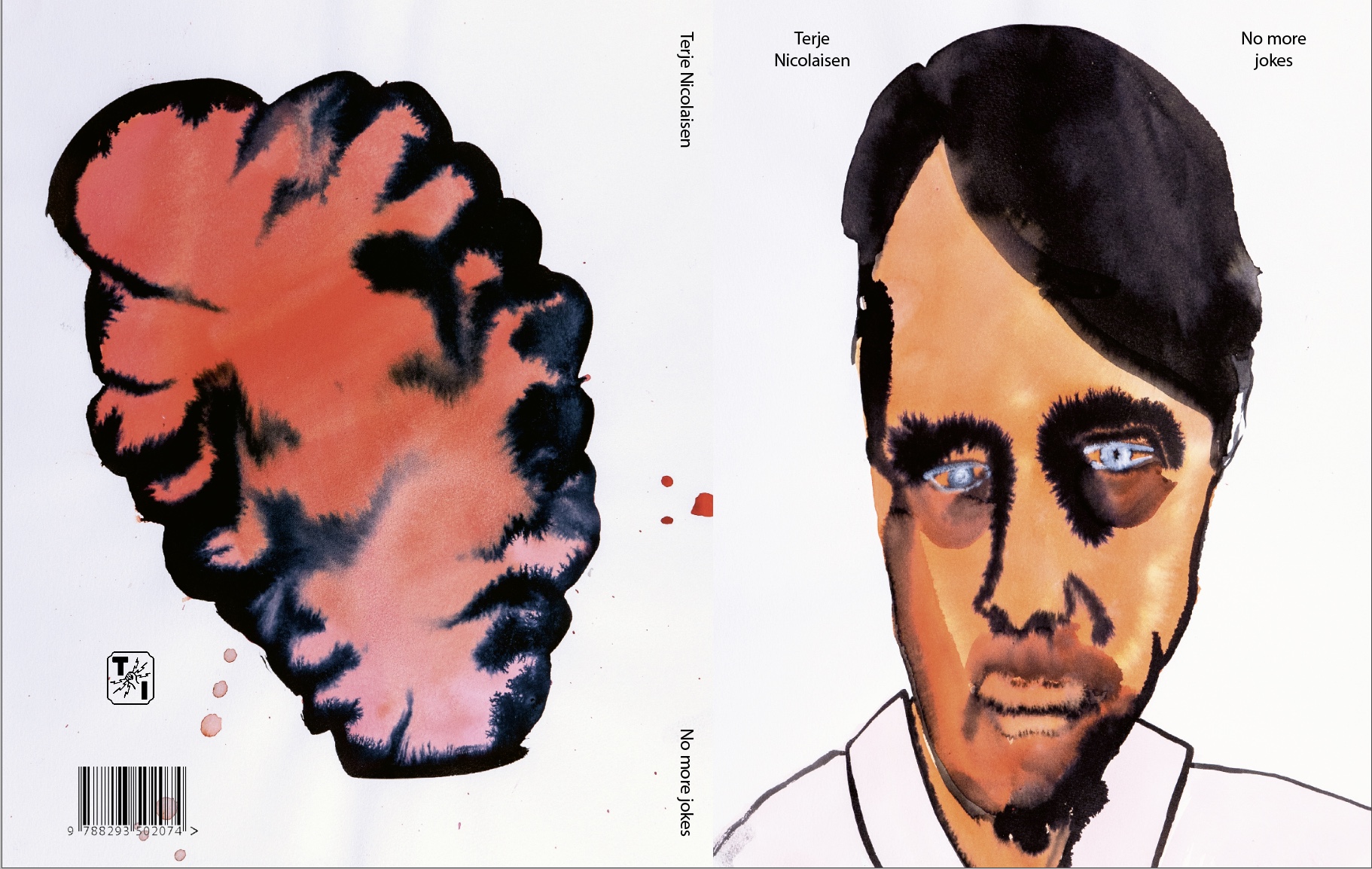

New book released on KERBER Verlag;

Terje Nicolaisen

No More Jokes

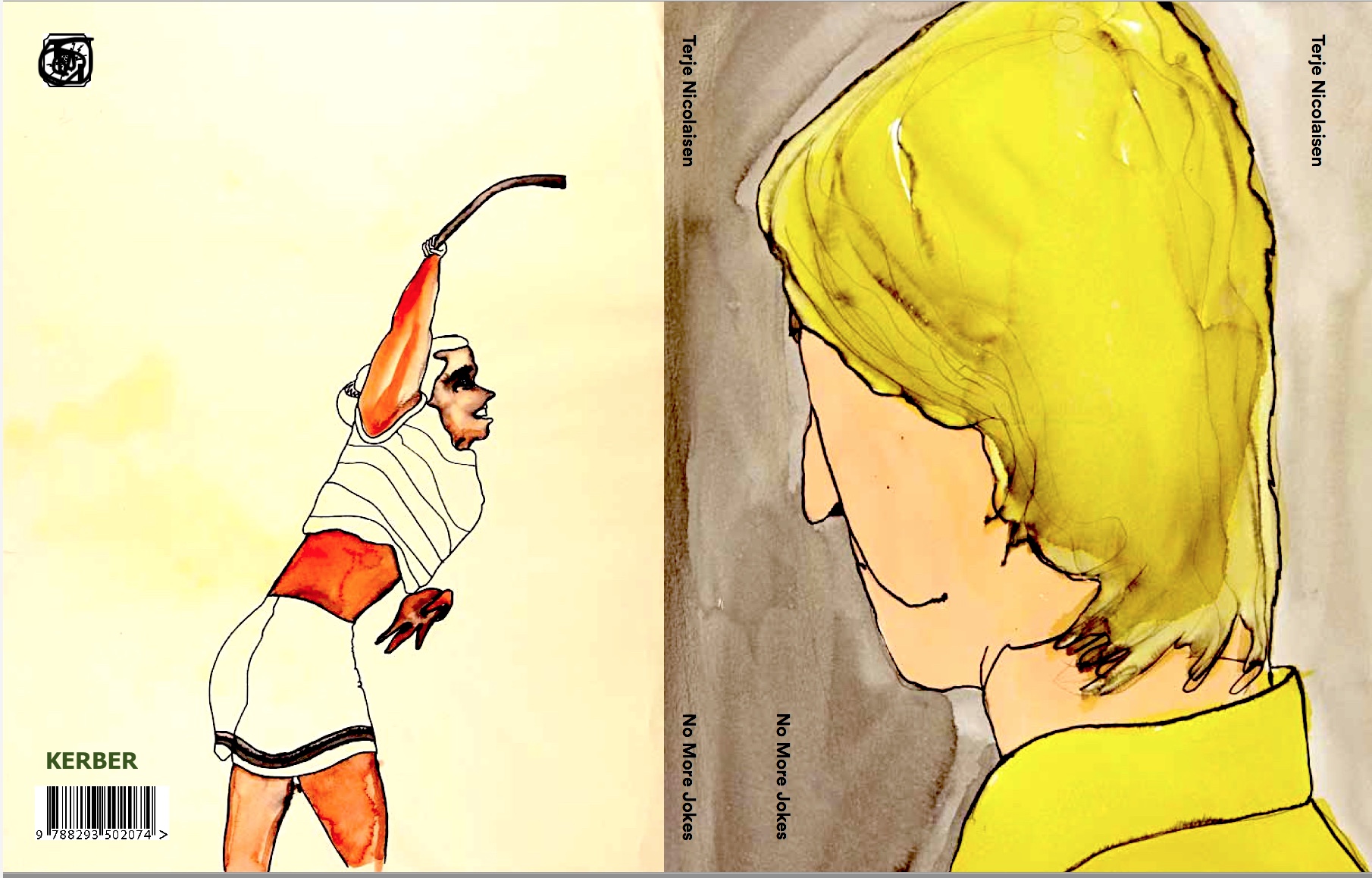

The art of Terje Nicolaisen (*1964) strikes a fine balance between sincerity and mischievous irony. No More Jokes emphasises the former through works on paper that constitute a different vein of Nicolaisen’s production, otherwise renowned for conceptual works in the tradition of institutional critique or dealing with public space, always tongue in cheek. Nicolaisen’s skilled treatment of paper and pigment, most notably in portraits of characters both familiar and fictional, is abundantly presented in this first internationally published volume.

Preface - Johanne Nordby Wernø

No More Jokes is meant to offer an immediate and honest entry into the body of work of an important Norwegian artist. The book does this through a selection of works that cultivate a sincere, modally strong and visually interesting vein in an increasingly brave Terje Nicolaisen.

A common feature behind many of Nicolaisen’s artistic strategies is that it may seem like the artist subject – through various means – reserves or protects himself. Throughout his nearly twenty-year-long oeuvre, the relator has often hedged his bets against criticism through extensive joking; unabashed and charmingly, he evades a final judgment. The production includes an abundance of humorous and/or performative works in a slapstick manner; institutional critique in texts and images, often as playful polemics against both global and local, named, actors, and their impact on power and resources in the field; and so-called proposals, suggestions for public artworks that cannot necessarily be realised. But when he avoids the sincere, serious or earnest, it is because of bashfulness and not cynicism. And this incompleteness – the slapstick manner, the internal references, and that which in any case was never meant to be realised – has served him well through a long practice.

As Nicolaisen now addresses his own tendency to not want to be “good at something”, he does so with a running start, risking not to crack jokes. In No More Jokes he is just good – extremely good.

The direction of the book materialised during discussions in the winter of 2017-18, when the artist and I, together, looked through scores of material on paper during a series of studio visits at his studio at Tøyen. We wanted to debate where the urgency lay at this stage of his life and practice.

Nicolaisen has thus explored – and/or actually felt – a denial of the “proper and substantial”, and instead perfected the sketch-like. An exception, where something “proper” has been touched upon after all, are the works where he assumes a persona that idolises and straightforwardly stalks – the fan. A human vulnerability shines through when the package he sends Neil Young is returned, unopened, or when major German artists politely turn down invitations to collaborate despite the sender Nicolaisen’s great efforts. Real idolisation is hard to combine with irony, to expose one’s admiration for, and interest in others, comes with vulnerability.

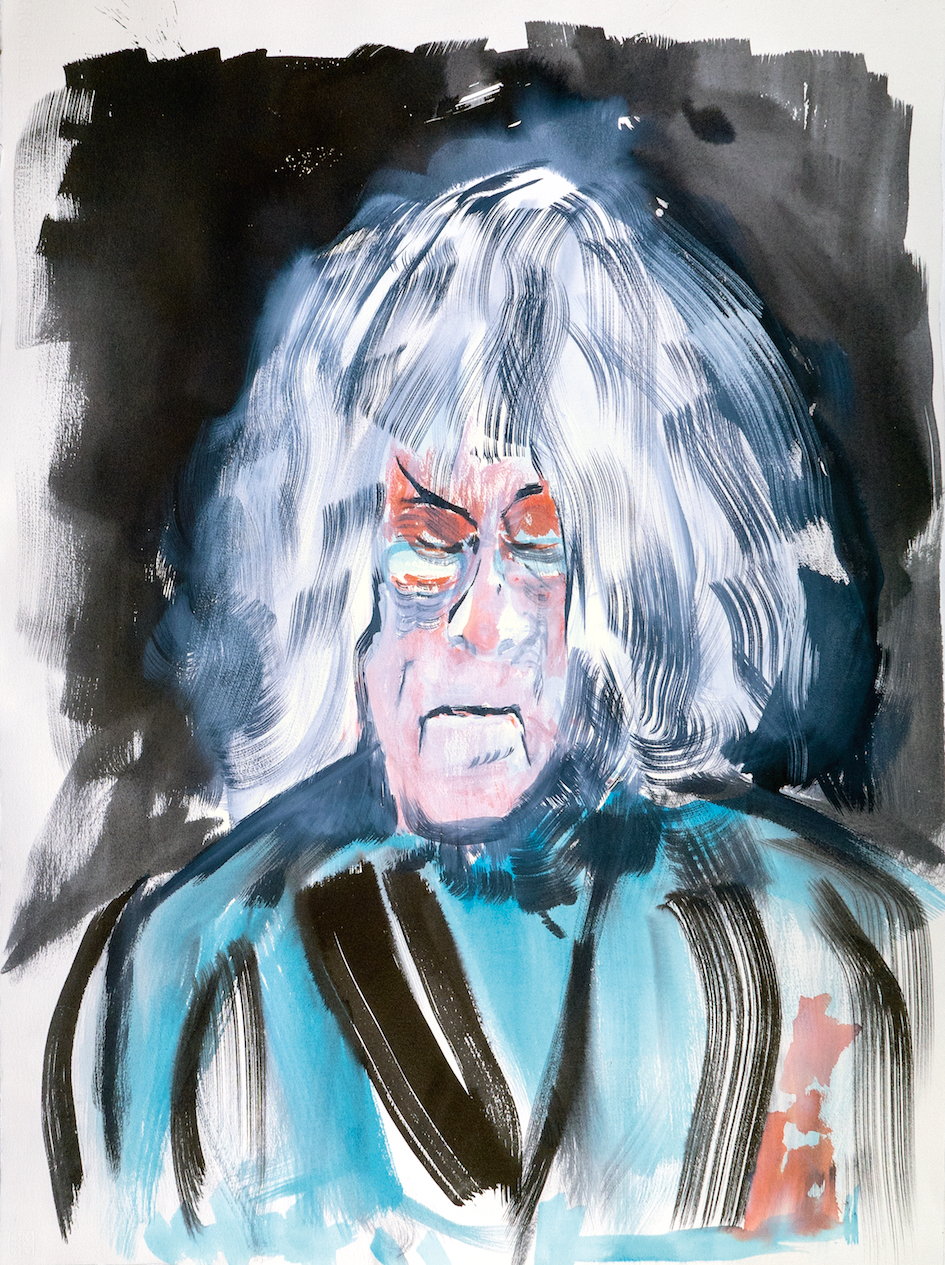

An abundance of portraits of those known and unknown is one of the book’s dominating genres. But the selection contains pointers to previously mentioned familiar veins in Nicolaisen’s body of work: the book is not completely stripped of jokes, and in many of the portraits, more or less influential people in the art world are depicted. The clue has, however, been to choose works based on criteria that are as simple as they are underestimated in the oeuvre, leaving us with material that was more than ready for its own presentation in book form: Terje Nicolaisen’s atmospheres, use of colour, lines, painterly qualities and the artist’s actual talent for form, colour and rich figurative imagery.

Johanne Nordby Wernø,

Oslo, 25 August 2018

BIO:

Johanne Nordby Wernø (1980) is an Oslo-based curator, critic and editor. Since 2000, she has published texts in Norwegian daily newspapers, and in Norwegian and international art presses. In 2013-16, she was Director of UKS/ Young Artists’ Society. She has also worked for the Norwegian Consulate General in New York and in editorial positions for Kunstkritikk.

www.jnw.nu

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Inner and outer faces by Terje Nicolaisen - Kjetil Røed

“The face is not merely an image but also produces images.”

– Hans Belting, Face and Mask: A Double History.

“What then is our face if not a ‘citation’?”

– Roland Barthes, Empire of Signs.

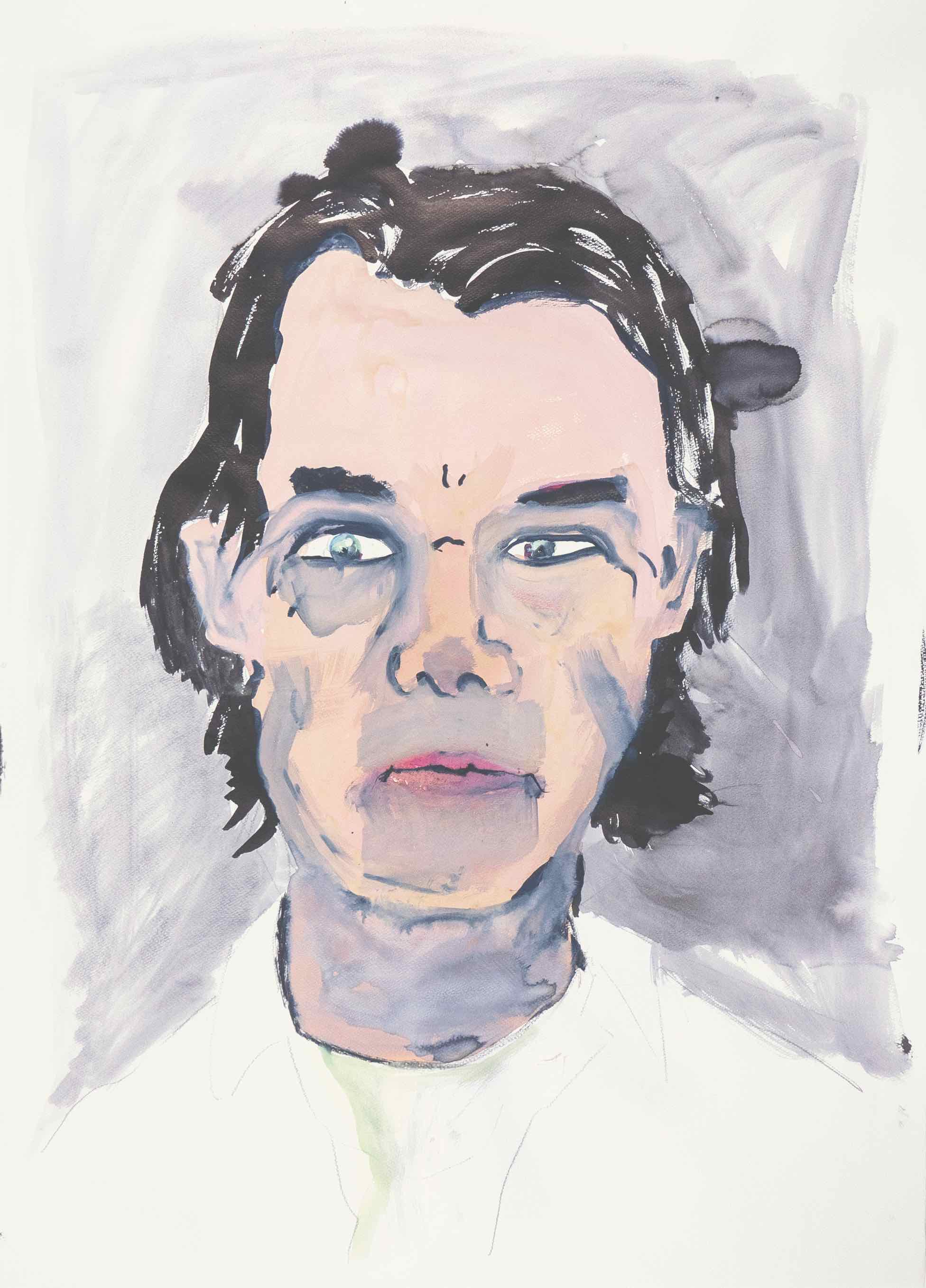

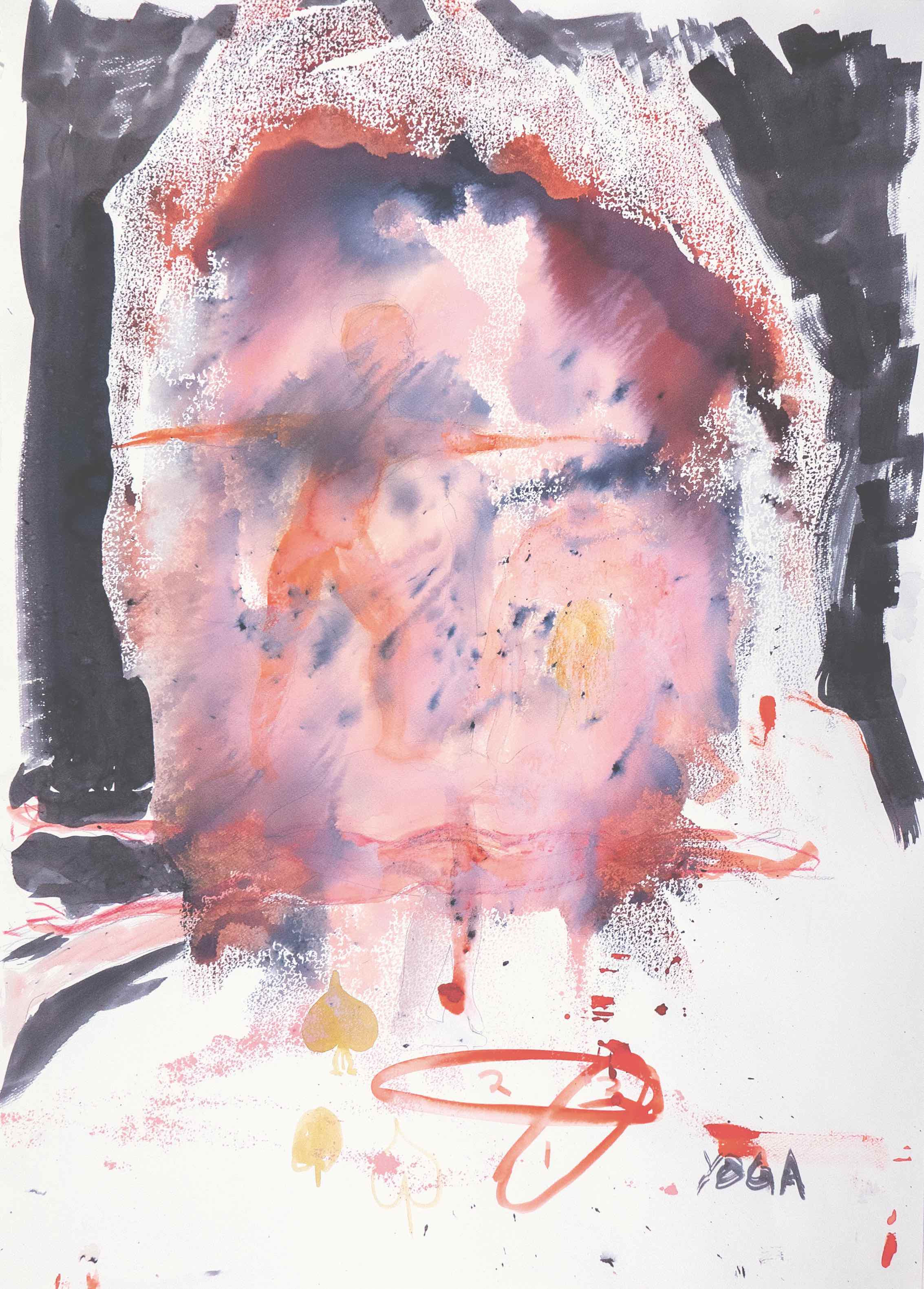

As I flip back and forth through No More Jokes, it is the frailty of the faces’ exteriors that strikes me the hardest. Terje Nicolaisen maps out different characters and their surroundings, in a way that touches directly on who the portrayed in the deepest sense are. Not as a concluding description, not as a list of qualities, but by emphasising that we are in need of something else than what we have become accustomed to if we are to understand the individual human being.

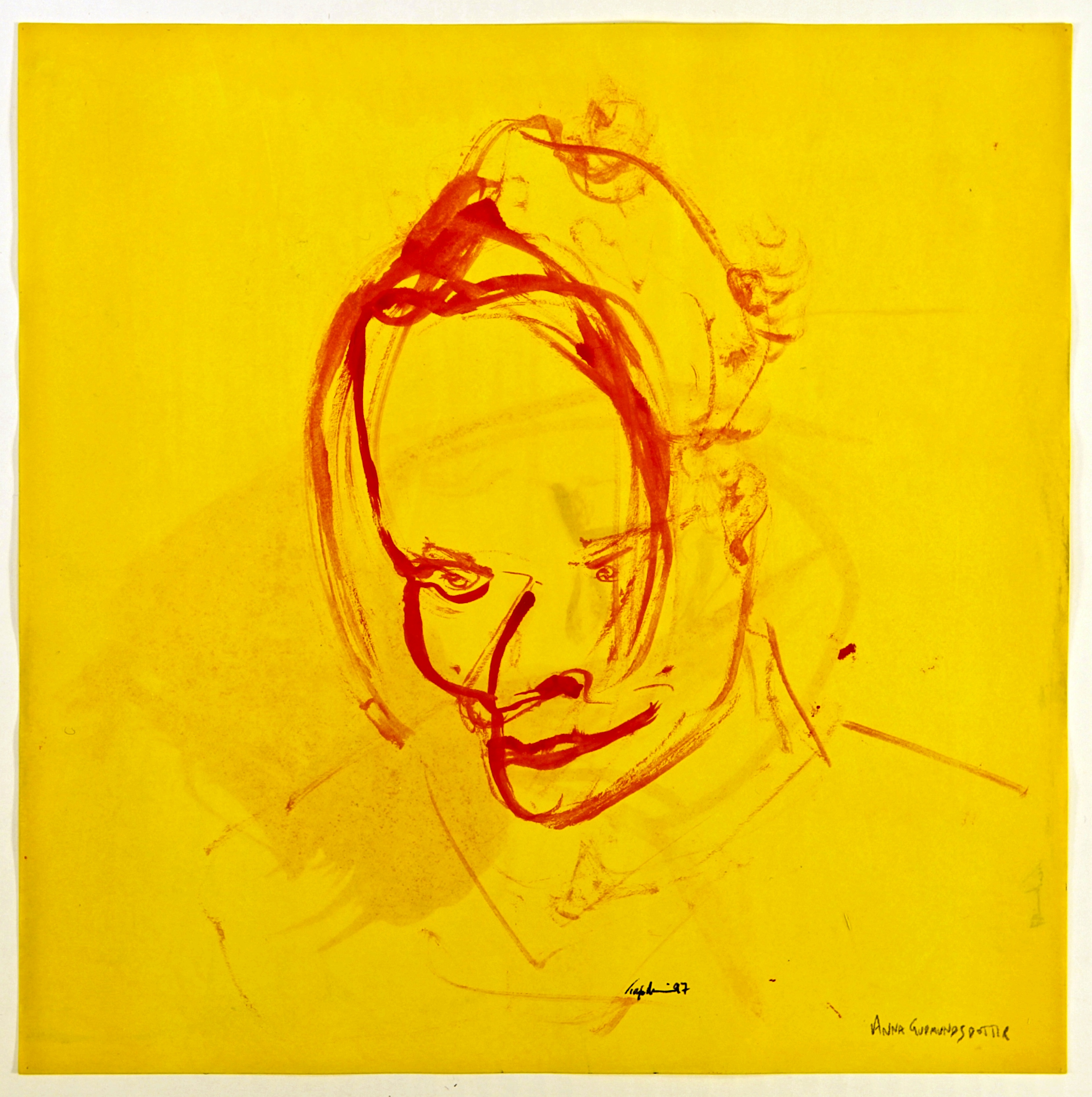

In Nicolaisen’s Dag Solstad (2017), the author’s hair gets a wild life of its own – it resembles a waterfall or an expressive landslide of white, flipping the portrayed out of the stabilising author persona that is usually communicated through images of him. His face is porous, airy and saturated by other forces than the coordinates that keep “Dag Solstad” visually in place as a public figure that we recognise and know. In Virginia Woolf (with fold) (2007), the famous author’s face is about to disintegrate from within: her skin colour is consumed by signal yellow, and shadows and hair accessories grow into moss-like dots or waterlogged sponge formations, which, together, drag Woolf out of the generic format that frames her authorship in a finely-tuned gravity and a delicate, strong beauty. Nicolaisen’s picture of the author and protofeminist unlocks a repertoar of forces behind Woolf’s habitual surface, which actively works on the outline of the face’s relationship to the actual person and pulls her in different directions. For example, we can consider the portrait as something that has been dragged into natural processes about to consume the image: as if humidity and mould are just behind the frayed paper surface for in the next instance to sprout through and absorb Woolf’s appearances. In both instances – with both Solstad and Woolf – pressure is put on the symbolic value of the recognised, familiar, faces of the authors. It is about unlocking famous portraits that have been locked into a pose or idea, or even make the face a scene of visual experimentation and reflection.

The identities of the people we are introduced to in No More Jokes play out in the artwork itself, as Nicolaisen attempts to locate the concealed asymmetries or points of disintegration that enable him to reinvent our gaze on the people we encounter. The works are optical laboratories, where the purpose is not to achieve precise likeness, but to make the artwork a site to contemplate who someone is. The paper becomes a stage. The colour bleeds or shines a light through the lines, creating an unruly pulse or bursting line, so that the open shapes of the faces and sprawling outlines of the bodies awake a curiosity that will not be satisfied. I like that this identity matter is not rooted in characteristic features, recognisable gestures or well-known mimics, but vice versa: by releasing elements that move the face out of position as something representative.

There is a sensitivity to these drawings that stimulates the curiosity about what the relationship between a human being and its face really is. In this way, Nicolaisen also creates a scene to experiment with different dramas to clarify his own identity. When we see authors and artists, it is namely often the artist’s own face that, directly or indirectly, lies underneath the other’s traits. This is seen most clearly in the works where the face doubles like two identity-bearing masks, literally pushed on top of each other, like in Dale Cooper (selfportrait) (2018) and Dale Cooper (selfportrait dobbeltganger) (2018). The artist has placed his own face on top of Dale Cooper’s doppelgänger, that is, a doubling of a figure that already connects two faces, since Cooper in Twin Peaks is personified by the actor Kyle MacLachlan. This multiplication of both Nicolaisen and Cooper does not lead us to similarities between the artist and actor (or character), but rather a Janus face that is pulled in different directions by identities without clear markers, since we cannot pinpoint exactly where one face begins and the other ends. These are polyportraits, where it veritably seethes in the visual tension the faces have ended up in. To force something together that cannot be reconciled keeps the elements open and initiates reflection on who the individuals are, based on how they appear.

But when are the masks on and when are they off? Is there a difference at all? We like to think that the face is the most genuine form of expression (the medium) to convey who we are. And it reveals something about us, no matter if we want it to or not: it is the body’s archival system, a biographical tachograph. Our life stories modify the flesh by making an entry of events and repeated mimics, like narrative marks on the face (wrinkles, sagging skin, scars, bruises, and so on). The mask, on the contrary, is something that we put on – something false and simulated, but also frozen in one expression. Therefore, we are not identical with the mask, it is something external, a shell without obligations because it is not us, although it reveals something general about human beings through its stylised features. It is not individualised, but a materialisation of typologies, general emotional states like grief and happiness. Typologies are a shortcut to the defining states of human life, but they can also, which Nicolaisen demonstrates in this book, be used as a starting point for further processing and review of a particular face.

Just look at Nicolaisen’s portraits of himself as a writer: the reflective posture behind the desk with the obligatory dishevelled hair and aslant cigarette and an analogue typewriter in the foreground, which places the production in a media-technological past, a couple of decades (or more) ago, when the “writer” was purer and still untarnished by the digital age’s Facebook procrastination and word processing’s promiscuous copy-paste writing. This is the author as myth but also as citation. In Empire of Signs, the French philosopher Roland Barthes speaks of the experience of seeing his own face reproduced in a Japanese newspaper: it was “japanified”, his “eyes elongated, pupils blackened by Nipponese typography.” Shown on the facing page is the Japanese actor Tetsuro Tanba, originally published in the Japanese newspaper Kobe Shinbun, posing tough and brashly, an attitude that, according to Barthes, cites the Western actor Anthony Perkins' characteristic mimics. In the reproduction, “he has lost his Asiatic eyes. What then is our face if not a citation?”, asks Barthes. We could answer him using Nicolaisen’s drawings, which show us that the unresolved state between individualising faces and the mask’s citation can be left open, so that the transitions between them remain at a standstill, in a tension that cannot be resolved as one thing or the other. Barthes’ reflections on the body, face and identity are interesting in this context, as he tries to liberate himself from the closed relationship between them.

The artist’s staging of himself in At The Bar (2018) – where he looks like, exactly, Barthes (a citation?) – repeats another typology (the bohemian), but is modified by the visual sincerity of the face and body. The figure has cracks and slits and is characterised by a slope that prises the scene open, so that the figure’s pose fails in keeping the portrayed artist inside the drama he is depicted in. There are fluffy shapes in the background, which, due to the watercolour, bring both the characters and the interior behind the protagonist into a fluid state. Yet again, I cannot help but think that this dissolution of the face and the place’s solidity has to do with forces that threaten or destabilise the place and people’s identity – that the protagonist does not entirely believe in the role he has taken on, or that the people behind him, perhaps, would like to throw off their refined selves as café patrons and rather take their clothes off and scream. Any such scene is but a coating on various forces, wishes and conditions that at all times threaten to disperse the drama and the roles’ fine outlines. Here, the shape itself touches on these destabilising forces, they tear and toil on what comes into view, thus enabling us to think about the underlying unrest. Perhaps one could say that Nicolaisen liberates the face from the bodily unity that the West, according to Barthes, views the individual through? Mimics and gestures break free from the idea that we will see a particular person, without Nicolaisen sacrificing the composition’s premise: The wish to know who we are looking at.

Again, I flip back and forth through Nicolaisen’s watercolours and drawings and think that what was supposed to be a representation of something – a face, a body, a situation – is in this book, a visual adaptation that does not mind showing the faceless chaos directly – the disorder that threatens any external expression of identity with the loss of control, death, illness or decay. The terminal point for the conflict between the face and the faceless is found in the works that strip off the face’s patina to reveal the shapeless flesh underneath. In My People (2000), Summer Darkness (2005) and especially Careless Whisper (2005), it is as if not only the mask but the face itself is gone. The cited face has been pushed aside to the benefit of the forces an organised face usually has under control. Like the painter Francis Bacon so clearly showed us, it is the impersonal flesh that we hide behind the mask, which, like a civilising coulisse, covers what we share with animals. The violence that rises in the pictures are as disturbing as Bacon’s, since Nicolaisen shows the madness behind the mask, unveiled, both in this book and everywhere else. It is especially the fleshy and brutal chaos that gapes towards me in Careless Whisper that seizes me with its intensity, but at the same time I wonder if the work refers to a song by George Michael that I cannot stand. I dig out the lyrics, which without Michael’s placating honeyed voice surprises me by instead empowering the brutality opened up by the flesh unfolding in front of me. The depiction of lost love tells me that whispering is inconsiderate, as it conceals infidelity with fake sympathy. The mouth’s crooked whisper in Nicolaisen’s drawing still takes it a radical step further, being robbed of human refinement. He (or she) can no longer control the application that becomes entwined in a whirl of flesh, where the faceless underneath punctures all order.

It is evening and once again it is snowing outside the office windows. Inside, in the heat by the desk, I cannot stop looking at Nicolaisen’s drawings. They tug at the masks I wear myself and if there is something they make visible, it is how frayed our faces often are. At the same time, fortunately, he says that it is easier to find a face with long-lastingness when we become aware of its frailty. It is about being sincere and overtly curious about oneself and others. Just like Nicolaisen is in this book.

For press images please contact terjenicolaisen(the alpha)gmail(the punctuation)com

Nicolaisen has a rich and diverse creative activity behind him, with conceptual works that deals with

everything from institutional criticism, proposals for public projects, installations, performance and music,

often conveyed with a humorous twist.

The book No More Jokes emphasizes another and more sincere vein in Nicolaisens art, where his distinctive

portraits of known and fictional characters make up the main source. Through moods, color usage, lines and

picturesque qualities we meet Nicolaisens strong talent for form, color and figurative richness.

No More Jokes contains a biographical text about Nicolaisens artistry of art historian Tina Rigby Hansen, as

well as an analysis of the artist's portrait work by art critic Kjetil Røed.

The book was edited by critic, curator and editor Johanne Nordby Wernø, and the design is by Ulf Carlsson. The book is published by Kerber Verlag (Berlin) and is the first internationally published book about Terje Nicolaisen's art.

Terje Nicolaisen (1964) lives and works in Oslo. He has been purchased by, among others, the National Museum, the Munch Museum and KODE Bergen Art Museum and has had solo exhibitions at Henie Onstad Art Center, Galleri Riis and Kunsthall Oslo.

Johanne Nordby Wernø (1980) is a critic, curator and editor residing in Oslo. She has published texts in Norwegian and international press since 2000. In the years 2013 to 2016 she was head of the Young Artists' Society (UKS). She also has worked for the Norwegian Consulate General in New York and in editorial positions for the journal Kunstkritikk.

Tina Rigby Hanssen (1971) is an art historian, writer and curator. She has a doctorate in art history from the University in Oslo and a curatorial study from Konstfack in Stockholm. Currently, she is an academic advisor on contemporary art with Norwegian Encyclopedia. She has published articles on art and sound art in eg. International Journal of Performance Art and Digital Media, The Soundtrack and

for Soundeffects.

Kjetil Røed (1973) is a critic and writes about art, film and literature in a number of magazines and newspapers. He has been art critic for Aftenposten (2010 - 2017) and currently writes for Vårt Land. Røed is the editor of the trade journal Visual art and publishes two books in 2019; Working Through The Past (Skira Forlag 2019) and Art and Life: an instruction manual (Flamme Forlag 2019)

Press: Michelle Jelting

presse@kerberverlag.com

+49 (0) 521 95 008 15