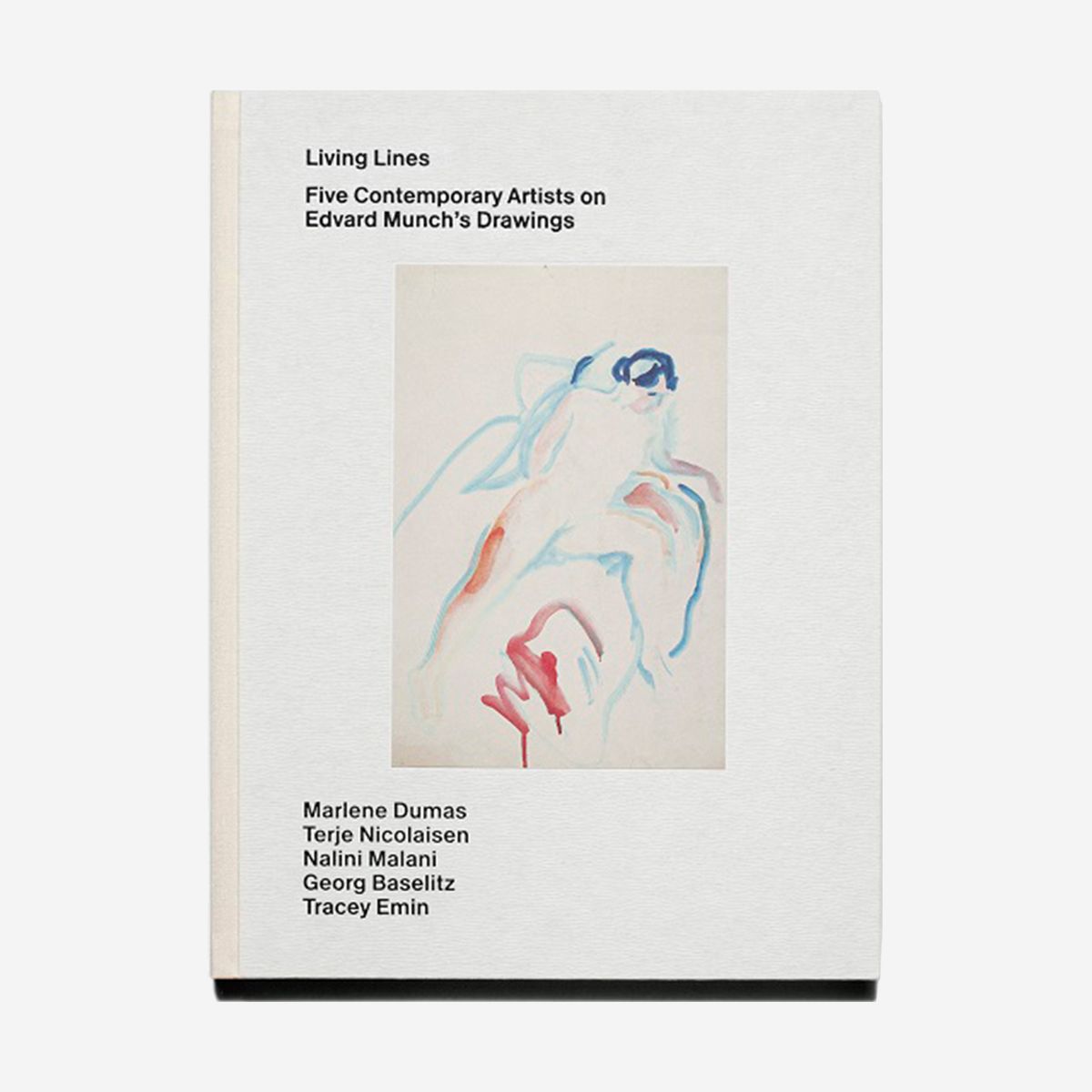

5 contemporary artists on Edvardt Munch archive of drawings

In this book, the five prominent contemporary artists Marlene Dumas, Terje Nicolaisen, Nalini Malani, Georg Baselitz and Tracey Emin have each put together a selection of Edvard Munch's drawings.

Munch drew more or less daily throughout his long life and left behind around 7,700 drawings. Each of the five selections provides a unique introduction to this rich material and is presented together with an interview, in which the artists reflect on Munch's drawings and their own artistry

Excerpts from an interview in the book Living Lines, done by Halvor Haugen (Editor)

THE SAME FREE, INTERESTING ZONE

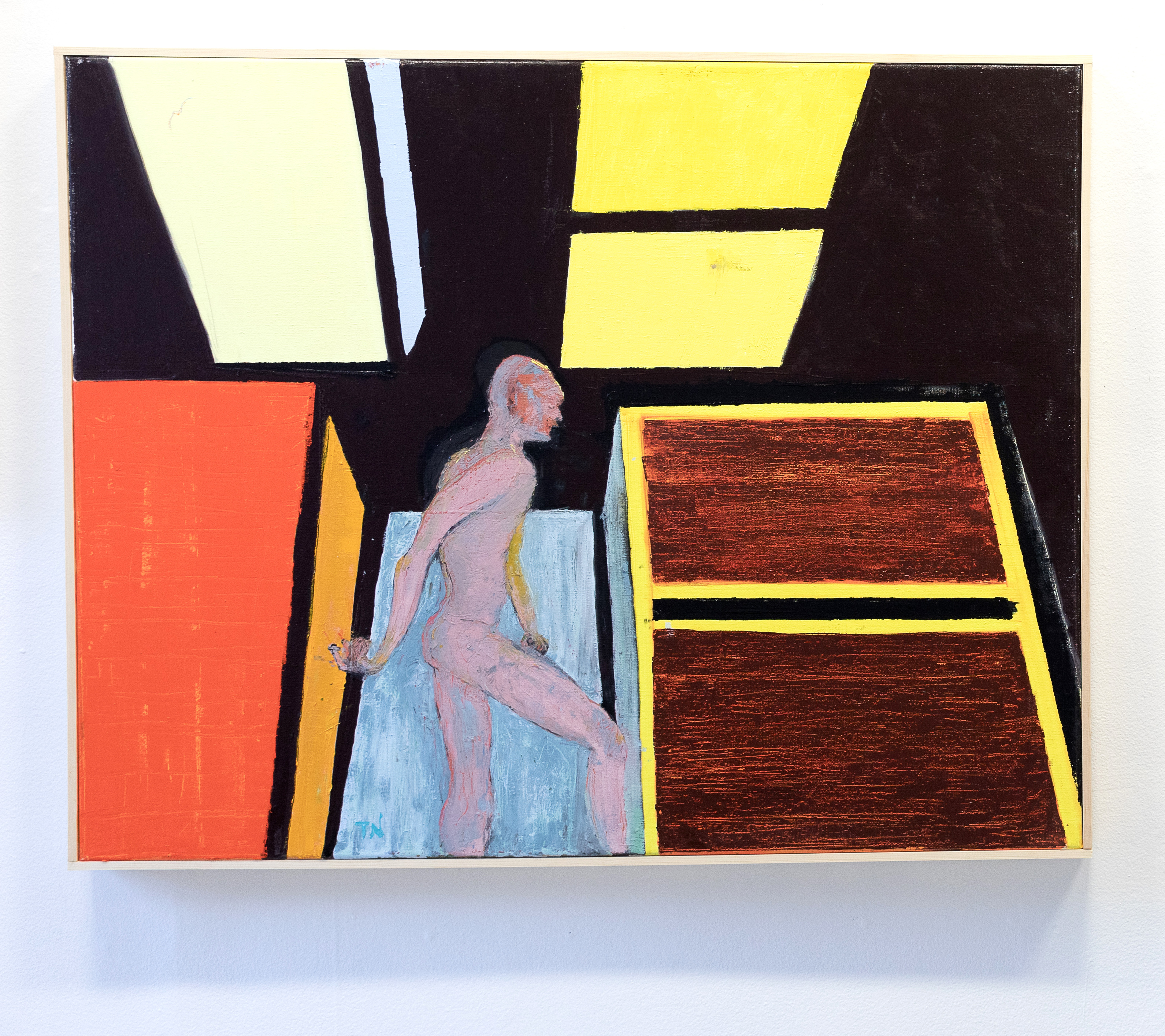

In Terje Nicolaisen's artistry, drawing serves as an effective means against pretensions. The large production of paper work records a mixture of spontaneous whims, accidental missteps and the occasional stroke of luck. Nicolaisen is known for proposals for unrealized art projects, uncensored everyday observations and portraits of both famous authors, other artists and acquaintances. In the selection of Munch's drawings, he has looked for modest points of similarity with Norway's decidedly most canonized visual artist - it is about those moments when you stumble and escape yourself.

I would like to think that Munch evokes a certain nervousness in many artists, perhaps especially in Norway. Is it like that for you?

No, I don't actually have a difficult relationship with Munch. For me he is a friend or at least an inspiring type. I have a studio right next to the Munch Museum and I often visit and see the exhibitions there. Munch always surprises me; I'm constantly discovering things I haven't noticed before. He also has a number of careless, slightly limp brushstrokes, and I have found great comfort in that.

But I must also say that Munch and I have completely different starting points. He was an incredibly good draftsman from the time he was a boy, and he also came from a culturally strong family. I trained as a bricklayer when I was young before starting the art academy. I came from artistic obscurity and slipped straight onto a stage where I didn't know the rules. I would say that I meet Munch where he stumbles, although we stumble in different ways. After all, he does it on purpose to get away from his own cleverness, and often succeeds in doing so. I don't have any of the skills he has; when I stumble, it's because I'm really trying to make something nice, maybe even something good. But I have no chance. So as he comes stumbling down the stairs, I try to get up. And then we'll meet there, then, at the break.

What did you look for when you selected drawings by Munch?

First of all, I have been looking for something other than the canonical works. I have steered clear of the finished, that which has a clear purpose, and I have also not included the illustrations, caricatures or studies of the more well-known works. So there are an extremely large number of the pictures I love, which I have just cut out. Instead, I've been looking for things where I feel like we're sort of on the same level. Don't get me wrong: when I say we're on the same level, it's about this tripping on the stairs. I have felt: Is this too precise? Is it too good, or too funny?

TRANSPARENCY

Shall we take a closer look at some of the drawings you have selected?

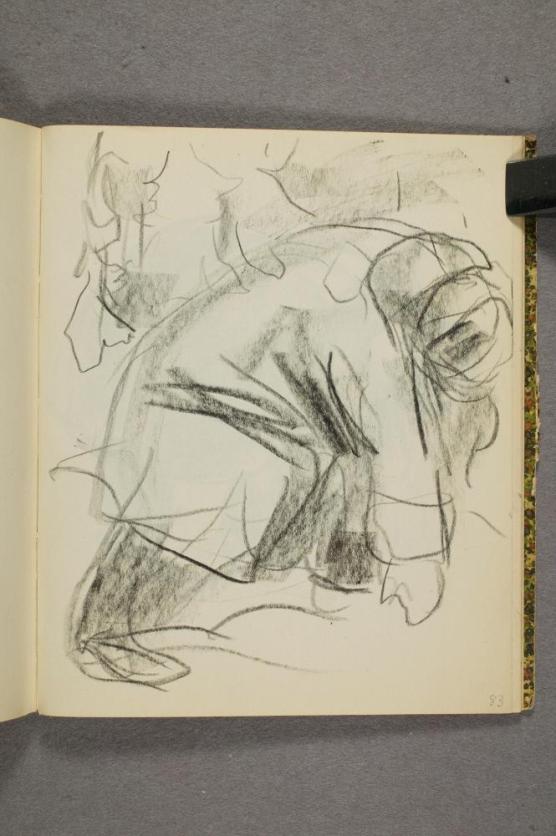

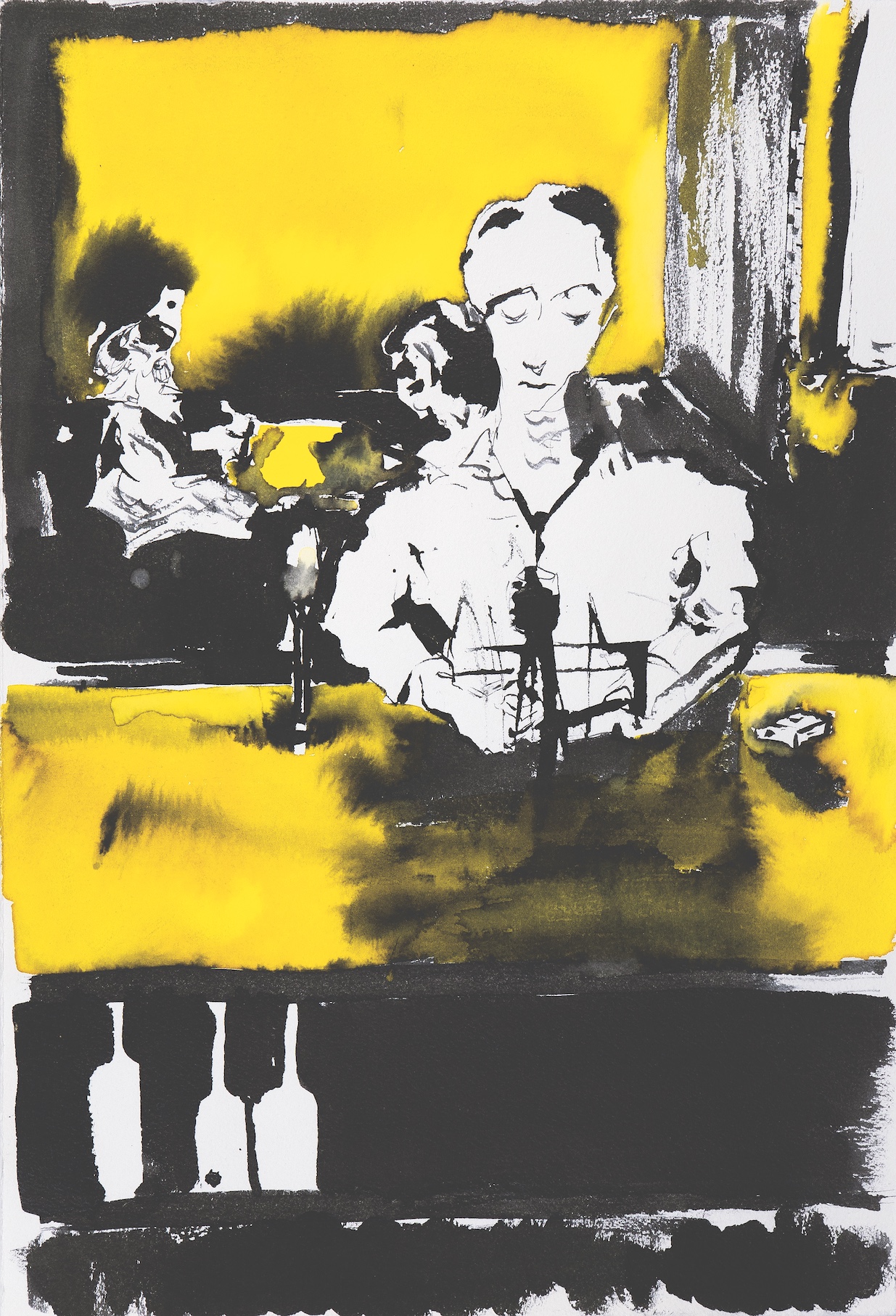

This one is lovely (Unidentified subject, 1916). Although it can be said that there is something here that resembles a human figure with two skies behind it, the purpose of the drawing is immaterial. The viewer can decide for himself what he sees. I think that a big challenge for all artists is to figure out how to keep an artwork open. With Munch, there is generally a lot of purpose; there is a story to be conveyed, and very often it is told so well visually that you are simply taken aback. But at other times he is looser, and the work becomes more open, so that you can enter it in different ways without sticking to his narrative. Before seeing the title Ragnarokk: Two fugitives on the beach, the elements in the image can be read in several other ways.

There are different types of openness in your selection?

In some of the drawings, he simply examines something, such as the map of the Oslo Fjord. You can call it an unintended drawing. It represents a space of thought. Here, Munch sat and thought about the geographical relationship between Oslo and Åsgårdstrand, but what remains is a figure that can also be read in completely different ways. This one, Man's head in front of a window, is more deliberately exploratory. I think he's trying to figure out how to place this person in the room, and he's very good at that. One eye is very intense and is right at the front of the image space. So he has tried it out: What is it like if the background is allowed to come through? I find that he tries to make things move back and forth. The background emerges through the face, pulling the figure back into the room. And it's fun!

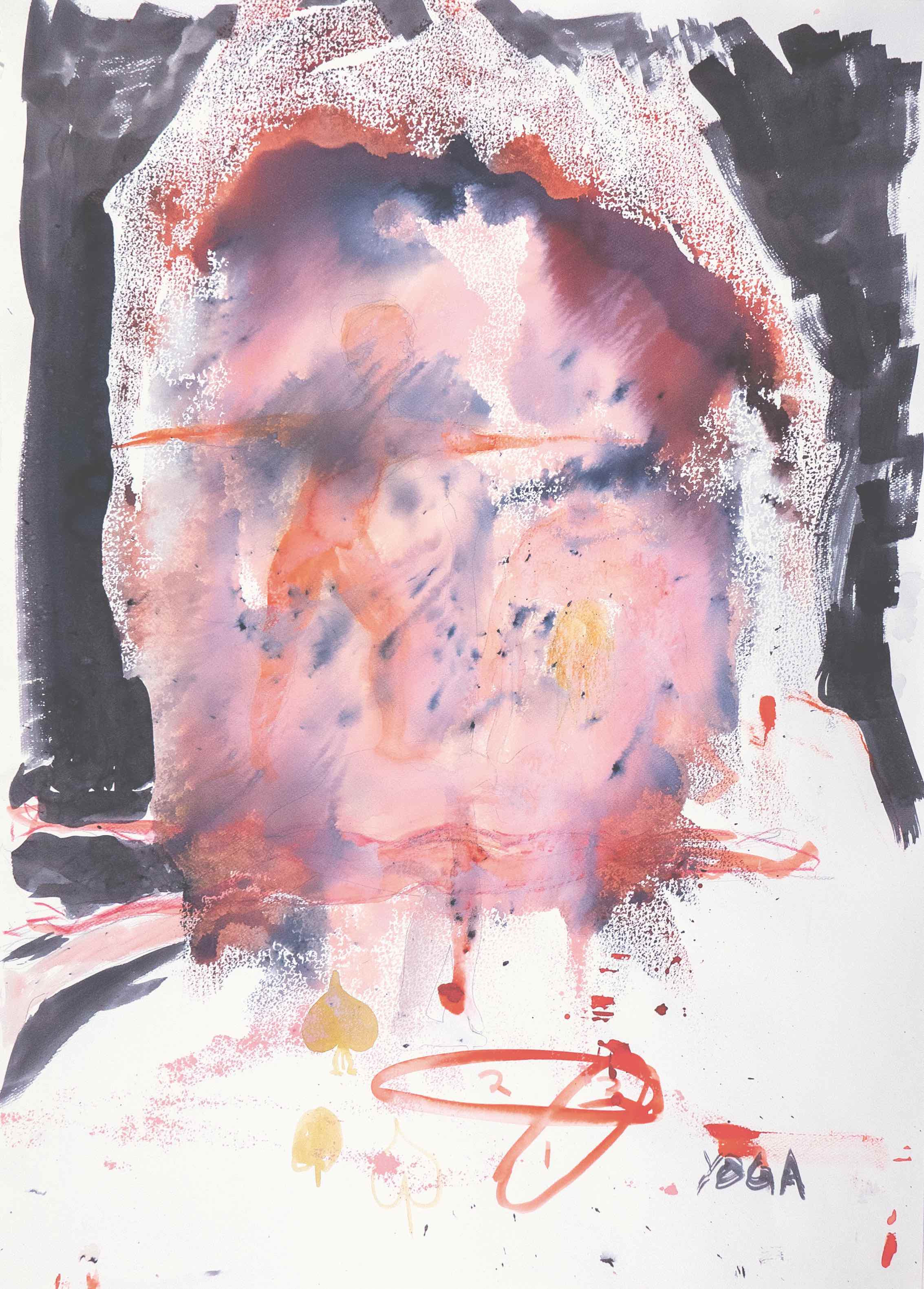

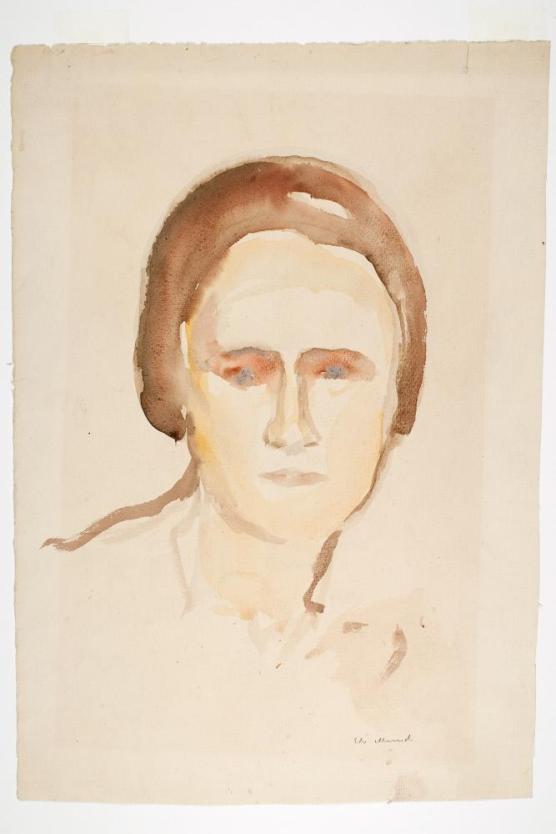

This female portrait perhaps has more of a suggestive openness that lies in watercolor as a medium?

Yes, things happen when you work materially, which you cannot predict, although you can control it to a certain extent through routine. On one side of her face it follows the red contour of the eye, while on the other side it has just settled in the corner, so maybe there wasn't enough water there? The hair is just a couple of quick coats. I think that here it is completely irrelevant who is portrayed - the picture owns itself.

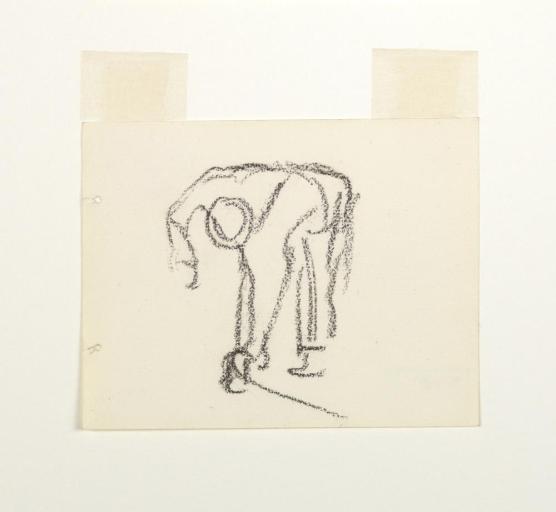

BENDED MEN

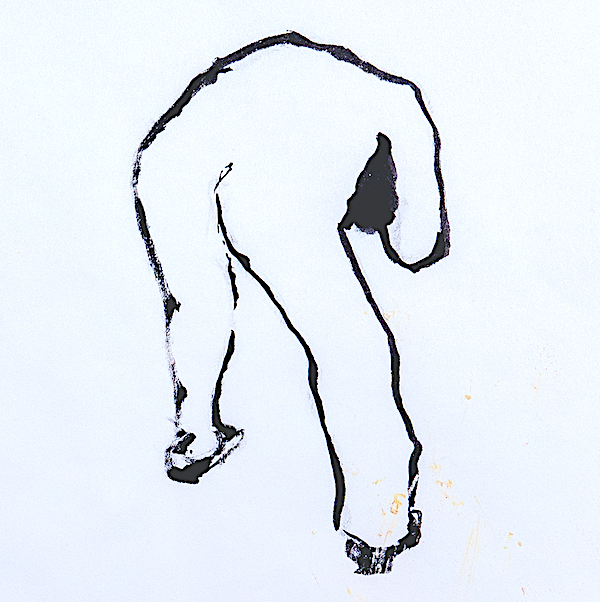

There are many bent male bodies in the selection?

The drawing of the man in front of the mirror (x) is as if made in a thinking phase, before the purpose is clear. Munch examines the figure's relationship to the mirror, without any clear symbolism or a finished joke....

Exerpts

With the two workers (x and x) I felt an immediate recognition; it is the dance that the workman—a mason, I imagine—does, day in and day out. A bricklayer makes approximately 1,500 such bends during a working day. No wonder my back hurts.

You also have a drawing with the title Handicrafts.

Yes, here he has probably not succeeded with a clear representation of a fisherman at work, and there is not so much there that guides our reading of the man's feelings. You can really just as easily imagine that he is a slightly clumsy guy as that he expresses stress and anxiety, or you can perhaps even read it as small-town romance. I thought that was beautiful.

The drawings of Foldal from Ibsen's play John Gabriel Borkman are a study of a body that bends for other reasons.

Munch's interest in this motif is interesting in itself, I think. After all, Foldal is only a supporting character in the play; a somewhat poor poet without any important role. In the last act, his daughter sets off with Borkman's son in a sleigh, and they almost run over Foldal, who is lying in the ditch. But these are drawings that don't really need Ibsen or the play. One has to find one's pictures somewhere, and here I feel that it was the body and the pose that were Munch's starting point; it has this fused togetherness that repeats itself in many of his pictures, including Double Act. Woman and man, half figure. It is more of an estimate than an actual study, and here it is the openness that attracts me again. After all, he hasn't placed their faces. She bows her head as if she is a little shy or perhaps coquettish, but the relationship between them is only slightly hinted at. There can be so many short stories.

The fused also repeats itself in the landscape drawings?

It is an incredibly cheeky and elegant representation of a group of trees. He just tows it in. After studying all these drawings by Munch, I see all the trees around me like that, especially now in winter when the trees are leafless and thousands of branches form a kind of drawing. He draws in whole groups of trees and decides that this is one being, one shape in the landscape instead of ten thousand lines. A brilliant simplification.

MEAN AND GENEROUS

Munch's drawings of people he came across may well be a bit mean. It is one thing to strongly hate a dissenter, but to hold a grudge against your neighbour's dog for years after it died, as Munch did, is not very dignified.

Munch is an expert at showing us emotions. Some of his drawings are perhaps more mean or self-righteous, but you have to be allowed to do that. He is also hard on himself, as in the self-portrait where he looks very much like the dog of the neighbor at Ekely. When you are mean, you have also put something on the table, at least to yourself. It might sound a little strange to call it generosity, but I mean it in the sense that he is willing to share and admit his feelings, even if they are nothing to be proud of.

The fact that Munch did not throw away any of his drawings also has something generous about it. It is amazing that he, who was so proud, could take care of all this. He also worked very quickly, which I think is a great quality for artists. Not that those who spend a long time necessarily make bad art, but the fast, performative and experimental is often what appeals to me. Munch was extremely productive. On the other hand, I have also thought that although it may seem like 7660 drawings is a lot, it is not really that terribly high number; not if you include all the sketchbooks and scribbles in the letters.

How many drawings do you think you have yourself?

I've never counted, but 4000-5000 is for sure. And I have only sketched so far, only tentatively proposed certain works. If I'm lucky, I can make art for another 20-30 years.

IS THIS FUNNY?

There is a good deal of humor in the Munch drawing you picked out, even though you said you didn't want to include the caricatures.

No, I think the pure caricatures are simply not very funny. They have something strained about them, something almost silly. I think it only becomes funny when it's involuntary.

It is connected to this openness that we talked about earlier?

Yes, it belongs to the same free, interesting zone I am concerned with. You can't try to get there either, right, because then it's intended. But Munch fumbles, and he shares it with us. He's in on it, and then it becomes kind of funny, but with warmth.

I have worked quite a lot with humor myself. And it is complex and difficult. It's like when someone says: Tell a joke, then! It is very disgusting to receive such a request. It's no fun to be funny on command. Basically, I actually don't want to be funny. My funniest works are made with the greatest seriousness.

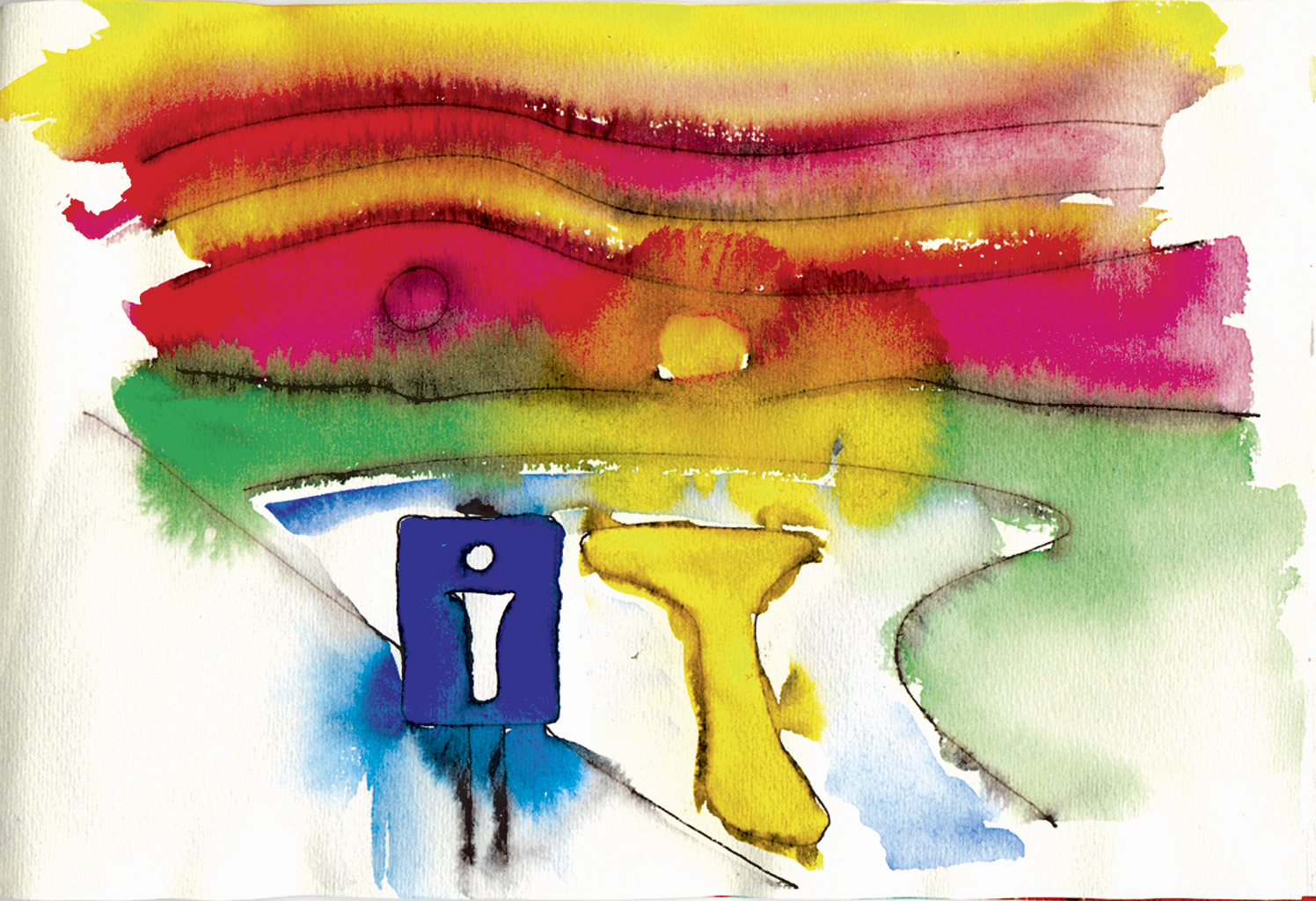

But what about your own work with drafts of projects and monuments. There you portray yourself as an artist who sits and thinks up quite distant things and thinks about how he can gain entry into the art world. Or your suggestion to turn Munch's famous moon pillars into an information sign (x) - isn't that a deliberate attempt to be funny?

It is intended in a way; I understand that many of these ideas cannot be implemented. But it's not like I'm thinking that now I'm going to make a book about an artist who tries to enter the art world and do all these things. It may be horrible to admit it, but I am actually the person who is trying hard to be professional, and who is trying to enter the art world, and I have made a lot of proposals and collected them in a book. So to the extent that it's funny, I guess it's because I'm actually that kind of person. The work on that information sign has an element of humor about it. But they are also about flagging that I am not that culturally versed; I admit that I got this slightly dusty idea when I looked at Munch.

TO ESCAPE HIMSELF

A question that has come up on several levels in the process of choosing among Munch's drawings is finding ways to work where one escapes oneself. But at the same time, surely the more assessing, contemplative side of you must be involved in the work?

It's a complicated question. When Munch hits, as he does in some of the pictures I have found, he has managed to get away from himself. Then he is just an actor with something in his hand – a charcoal pencil – who stumbles and brings about something that was not intended. And I may do the same, but I have been very keen to be free and be completely honest about the fact that I could not have drawn a realistic portrait of, for example, Dag Solstad or Allen Ginsberg. Even if I had done my best, it would have looked like something else entirely. I try my best all the time, and then I also try to admit this.

But both of those portraits are an example of a portrait that hits well, I would say. The comedy that occurs in Solstad's drawing is perhaps at his expense, but isn't it intended that way in the first place?

Yes, it's not a flattering portrait of Solstad, but it's certainly not meant as harassment - on the contrary, I'm a big fan of his books. I feel that the humor is also at my own expense, precisely because they somehow fall short. The drawing perhaps has something of the same give the fuck attitude that Munch must have found in several of the drawings in my selection - that moaning; you pull yourself into it.

Do you curate your own things in the same way as you have selected drawings by Munch?

I always struggle with choosing my own things. It is very difficult to separate the chaff from the wheat. When I have curators visit the studio, I am often very surprised by what they select; often it is what I myself have been ashamed of. The distance between what I myself think is good, and what others find interesting, has always been there. It is almost so that I feel unable to choose among my own works. Perhaps it is because the images are made with so little analysis. When I put color on a sheet, it gives me a kick that only I get. The consequence of the hunt for this kick is that there is still work to be done. But then I will judge it. Is it good? Can I submit it to the Autumn Exhibition? No, but then maybe nothing is good, really. Therefore, I have told myself that I cannot do that job. It's too complicated, at least if I'm going to make pictures at the same time. I believe that artists who have learned to be calculating while expressing themselves end up creating designs that look like art.

So there is a message in your selection?

In any case, there is a desire to show Munch as a trying, hesitating artist. Perhaps also that being clear about one's own is a prerequisite for being able to create art.

Details

Redaktør: Halvor Haugen

Forfatter(e): Mieke Bal, Magne Bruteig, Halvor Haugen, and Jon-Ove Steihaug

Forlag: Munchmuseet

Utgivelsesdato: 18.10.2021

Språk: Norsk

Antall sider: 240

Format: Innbunden

Størrelse: 240 x 320 mm

ISBN: 978-82-93560-70-8